Gehry: the genius who broke all the rules

DECEMBER 20, 2025

Luis Rodríguez Llopis

Presidente de IDOM

This is a transcript of the original article, which was published in the newspaper El Correo.

A tale of leadership and talent that signaled a pivotal shift

Bilbao, December 1992. A few days before Christmas, IDOM was awarded the project that would change the city’s history: the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. This marked the beginning of an exciting five-year challenge, and today, as we remember Frank Gehry, it is worth recounting.

In the world of engineering, architects, especially so-called ‘starchitects’, have always faced certain prejudices. They are accused of prioritizing aesthetics over functionality, ignoring constructability, and not caring about deadlines and budgets, as well as being more artists than technicians. Frank Gehry proved that these preconceived ideas could not have been more wrong.

IDOM took on the roles of executive architect, project manager, and construction manager. This involved adapting Gehry’s designs and those of his consultants to local conditions, ensuring constructability using local technology and resources wherever possible, and taking responsibility for financial control, deadlines, and quality. It was an enormous challenge.

I was responsible for managing the project throughout its five-year development period. We formed a team of over 400 people, many of whom were very young, and strengthened our architectural capacity by bringing in César Caicoya. He was an experienced architect who had collaborated with us on previous projects, and he played a key role in liaising with Frank Gehry and coordinating the design. It was an extraordinary collective effort.

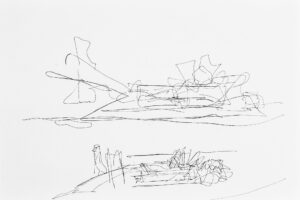

The Guggenheim Museum reflects Frank Gehry’s innovative character, not only in its bold forms, but also in the technology that made its construction possible. Gehry pioneered the use of advanced digital modelling tools, such as CATIA, which originated in the aeronautical industry, to define complex geometries that seemed impossible. He chose unconventional architectural materials such as titanium, now synonymous with the museum, and paid meticulous attention to details, such as stone carving, to achieve perfect integration of the contemporary and the timeless. This combination of creativity and technology marked a turning point in global architecture. For those of us who were fortunate enough to work on the project, it was a magnificent example of an innovative approach and a commitment to excellence.

The initial meetings in Los Angeles were tense. We undoubtedly had our prejudices, but architects also tend to have theirs about engineers, viewing them as insensitive to design, inflexible, overly simplistic and lacking in creativity. I remember a discussion about the contingency budget in the early stages, when uncertainty was at its peak. We argued for a high figure, but they thought it was exaggerated and attributed this to our lack of knowledge. It was a tough meeting.

But we soon discovered that the reality of Frank Gehry was very different from the clichés. In his daily work, he was the opposite of a difficult artist: he was friendly, approachable, and accessible. He was always concerned with maintaining smooth relations between teams. He listened to others, respected their contributions, and took on the client’s needs as his own. Contrary to the stereotype of the “star” architect, he was also interested in controlling the budget and meeting deadlines.

One of his most admirable traits was his ability to transform problems into opportunities. Whenever a problem arose, he would retreat to his studio, reflect on it, and return with a solution that improved the design and solved the problem. This approach made all the difference.

In large, complex projects, success is never individual; it is always the result of teamwork. Gehry was an extraordinary leader. He had an enormous capacity to communicate, generate enthusiasm, and align his team with the needs of the project. His decisive attitude, vision, and emphasis on teamwork and a collaborative environment were essential.

Interestingly, more than 28 years after the building’s inauguration and 33 years after the project began, many people from both teams are still in contact and have maintained friendships despite the distance, which is rare.

The Guggenheim’s success is undoubtedly due to Frank Gehry’s creative genius. But also, his humility, leadership skills, and respect for collaboration. As we bid him farewell today, we remember that his work transformed not only Bilbao, but also those of us who had the privilege of making it possible. He taught us that great projects are born when talent and teamwork go hand in hand. This is a legacy that continues to inspire Bilbao and the world.